German aerial photographer Tom Hegen documents landscapes transformed by human activity. In his upcoming project and book, The Mineral Age, he turns his lens to the extraction of raw materials that make the energy transition possible.

First, a very simple and logistical question: How do you decide where to travel next? How do you plan these trips?

I usually work on long-term projects that explore a specific topic relevant to our society and the environment. These topics often grow out of a broader interest in the human relationship with the Earth. Over the past few years, for example, I’ve been focusing on the energy transition, the minerals required for it, and how the extraction of these resources is reshaping landscapes worldwide.

My work is therefore strongly research-driven: identifying places that matter. Sites that are significant, representative, or extreme examples of these processes.

"Working there with a high-tech drone felt like two worlds colliding."

When you arrive at a site, what happens? How do you feel? Do you have a ritual?

Many of my recent projects take me to places that are remote or difficult to access. This comes with a substantial amount of logistics. Finding a local fixer, transporting equipment, and addressing safety concerns. I usually travel with a specialised drone capable of carrying a large-format camera, which often raises questions at airports and border controls.

By the time I finally arrive in a country or region, a great deal of work has already been done before the actual photography begins. Then, the real work starts. I adapt quite quickly to new environments. One of the first things I usually do upon arriving is take a walk through the surrounding area to get a sense of the place and its people.

What has been your most surprising interaction on site—a situation or person that changed how you saw the place?

A few years ago, I photographed salt production sites in Senegal. The salt farmers worked under the glaring sun, digging small canals that led saltwater into simply built evaporation ponds. It is extremely hard labour, often involving entire families. The work is done with bare hands and very basic tools. Donkeys and horses pull wooden trailers to transport both people and harvested salt across the flats.

Working there with a high-tech drone felt like two worlds colliding. Even though we didn’t speak the same language, the locals were incredibly open and welcoming. We even harvested salt together. Encounters like this have happened many times throughout my travels. They always remind me how much we share as human beings, even when our living conditions are worlds apart.

Do you sometimes ask yourself: “How did I get myself into this?”

Absolutely. Every project feels more like an expedition than a carefully planned holiday, always involving uncertainty. I regularly leave my comfort zone: sleeping in extremely run-down places, dealing with broken cars in the middle of nowhere, or solving countless small problems just to get the images I have in mind.

In those moments, I often ask myself what I’m actually doing and why. But when I return to my studio and look at the photographs I’ve made, I’m always amazed and I know it was worth the effort.

"When I started to look deeper into the topic and realised that this shift is one of the most significant transformations since the Industrial Revolution, with profound geopolitical consequences."

Can you take us back to the moment you realized you wanted to focus your new book on the energy transition?

My initial interest in mining came from a climate perspective, documenting where fossil fuels are extracted. Later, I began photographing some of the largest copper mines in Europe and the United States. While researching the mining sector and trying to understand how these materials are actually used, I learned more about the global effort to move away from fossil fuels toward a more sustainable future.

This future, however, relies heavily on other minerals such as copper, lithium, cobalt, nickel, or tin—which are essential for decarbonising our industries. That was the point when I started to look deeper into the topic and realised that this shift is one of the most significant transformations since the Industrial Revolution, with profound geopolitical consequences.

What’s something you only understood about the energy transition after seeing its origins up close?

Mining these minerals comes with major challenges. Many are extracted in regions with weak or non-existent environmental regulations, child labour issues, or severe impacts on local communities. Through working on The Mineral Age, I came to understand that the Global North is the primary consumer of minerals that are largely extracted in the Global South. Often in developing or underdeveloped regions.

This imbalance exists for several reasons: cheaper labour, weaker regulations, and, in some cases, simple geological distribution. The real issue is that we are once again exploiting resources from vulnerable regions to sustain our own comfort and keeping our own backyard clean. From a long-term environmental perspective, this path may still be better than our current fossil-fuel dependency, but only if we avoid repeating the same mistakes. That’s why I believe it’s crucial to put this topic on the table and help people understand the broader picture.

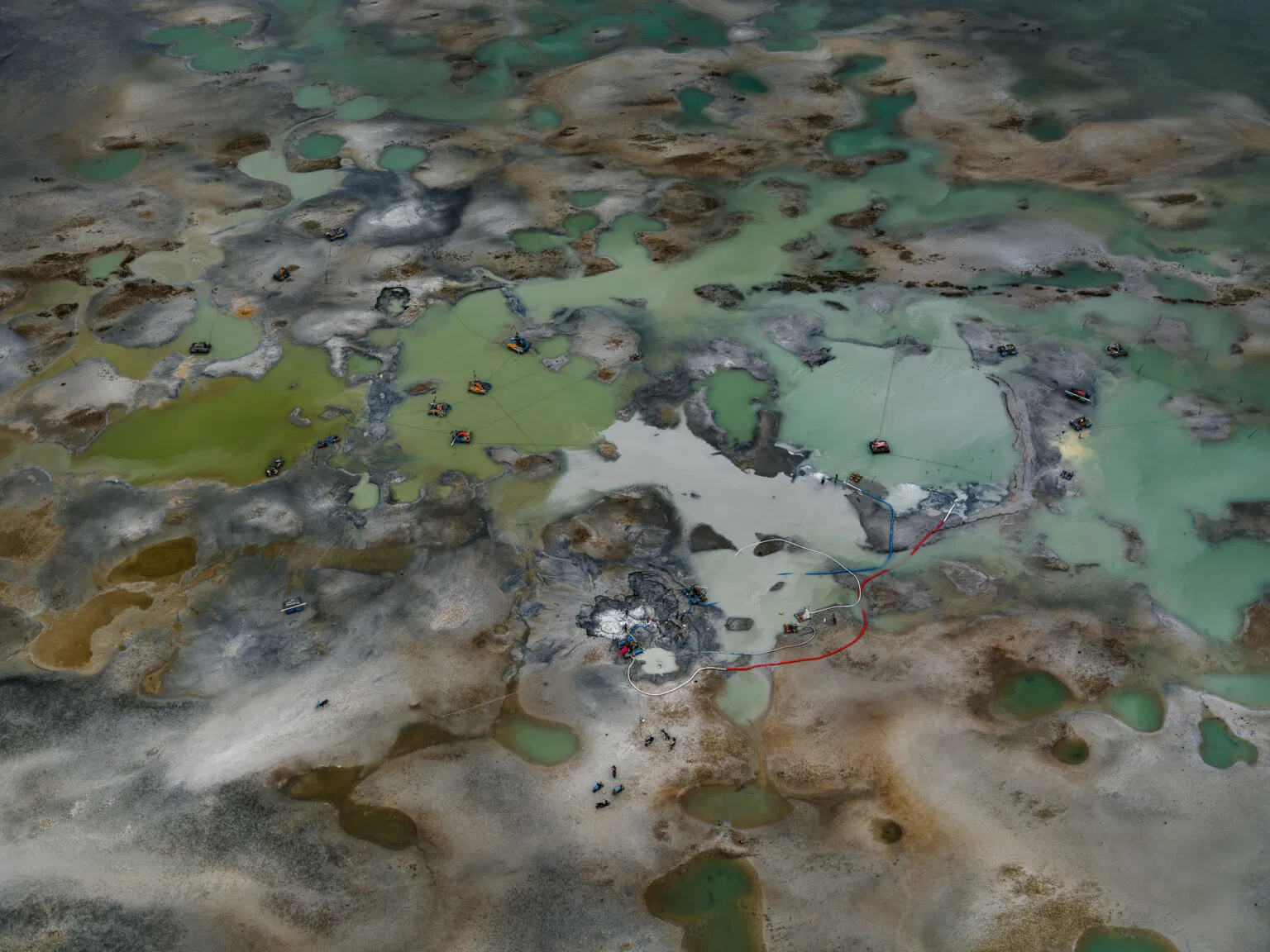

From left to right: Illegal seabed tin mining, Bangka, Indonesia; Nickel Smelter, Sulawesi, Indonesia

Has seeing these landscapes up close changed how you move through everyday life—even in small ways?

Absolutely. I’ve realised how much we in Germany, Europe, or the Western world live in a very comfortable bubble, cushioned by wealth and stability. I’m deeply thankful to have been born into these circumstances, and I constantly remind myself that this is an enormous privilege.

What’s one thing no photograph can fully capture about these landscapes?

The messiness and the true scale of these sites. Aerial photography can provide an overview and a sense of scale, but it’s something entirely different to experience these places firsthand. The dirt, the smell, the chaos, the risk, the corruption, and the destruction associated with these industries are things you can never fully grasp without being there.

If you weren’t doing photography, what do you think you’d be doing now?

I studied visual communication design, which I really enjoyed and initially imagined as my career path. Today, I’m grateful that I can work on self-initiated projects that help people better understand the world we live in. If I weren’t doing this, and could dream freely, I’d probably enjoy working creatively with my hands, using natural materials like wood.

Secret subtitle for your upcoming book—what would it be?

The title of my upcoming book is The Mineral Age – Fueling the Future. A more provocative secret subtitle might be The Dirty Truth About the Green Energy Transition. However, I prefer to remain more objective and allow readers to form their own conclusions.

Are you willing to share where you will travel next? What site will you capture?

As I’m answering these questions, I’m sitting in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo, where I will photograph the final chapter of the book: cobalt mining. It’s a project I’ve been trying to realise for nearly three years, and I hope that I can finally make it happen now.

Conducted by Irina Chèvre (Terraquota)